| Home Page | Editor Notices | Museums | Galleries | Publication | Donation | Contact Us |

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Orit Akta at Zemack Contemporary Art |

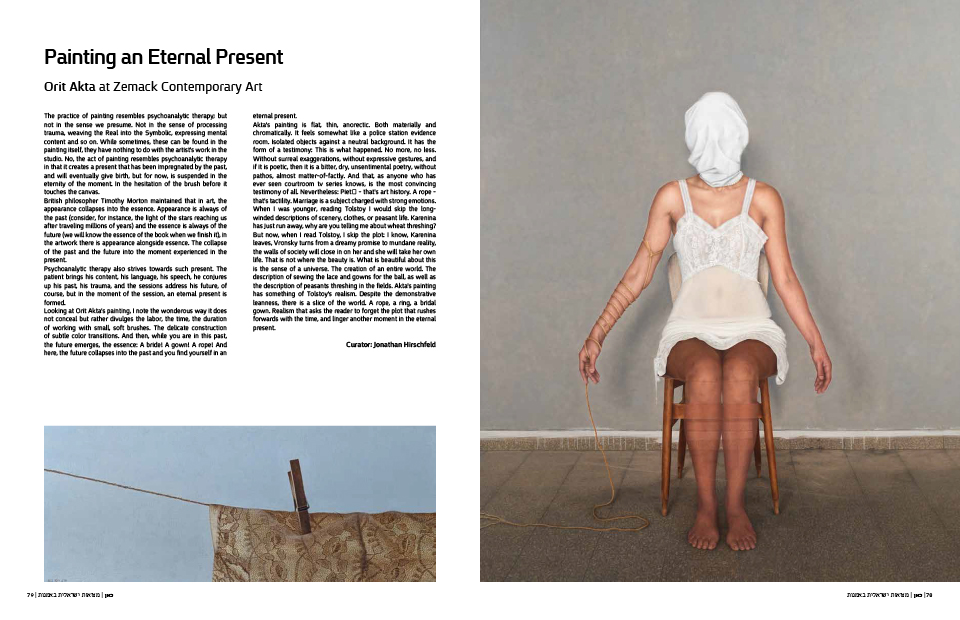

The practice of painting resembles psychoanalytic therapy; but not in the sense we presume. Not in the sense of processing trauma, weaving the Real into the Symbolic, expressing mental content and so on. While sometimes, these can be found in the painting itself, they have nothing to do with the artist’s work in the studio. No, the act of painting resembles psychoanalytic therapy in that it creates a present that has been impregnated by the past, and will eventually give birth, but for now, is suspended in the eternity of the moment. In the hesitation of the brush before it touches the canvas. British philosopher Timothy Morton maintained that in art, the appearance collapses into the essence. Appearance is always of the past (consider, for instance, the light of the stars reaching us after traveling millions of years) and the essence is always of the future (we will know the essence of the book when we finish it), in the artwork there is appearance alongside essence. The collapse of the past and the future into the moment experienced in the present. Psychoanalytic therapy also strives towards such present. The patient brings his content, his language, his speech, he conjures up his past, his trauma, and the sessions address his future, of course, but in the moment of the session, an eternal present is formed. Looking at Orit Akta’s painting, I note the wonderous way it does not conceal but rather divulges the labor, the time, the duration of working with small, soft brushes. The delicate construction of subtle color transitions. And then, while you are in this past, the future emerges, the essence: A bride! A gown! A rope! And here, the future collapses into the past and you find yourself in an eternal present. Akta’s painting is flat, thin, anorectic. Both materially and chromatically. It feels somewhat like a police station evidence room. Isolated objects against a neutral background. It has the form of a testimony: This is what happened. No more, no less. Without surreal exaggerations, without expressive gestures, and if it is poetic, then it is a bitter, dry, unsentimental poetry, without pathos, almost matter-of-factly. And that, as anyone who has ever seen courtroom tv series knows, is the most convincing testimony of all. Nevertheless: Piet? – that’s art history. A rope – that’s tactility. Marriage is a subject charged with strong emotions. When I was younger, reading Tolstoy I would skip the long-winded descriptions of scenery, clothes, or peasant life. Karenina has just run away, why are you telling me about wheat threshing? But now, when I read Tolstoy, I skip the plot: I know, Karenina leaves, Vronsky turns from a dreamy promise to mundane reality, the walls of society will close in on her and she will take her own life. That is not where the beauty is. What is beautiful about this is the sense of a universe. The creation of an entire world. The description of sewing the lace and gowns for the ball, as well as the description of peasants threshing in the fields. Akta’s painting has something of Tolstoy’s realism. Despite the demonstrative leanness, there is a slice of the world. A rope, a ring, a bridal gown. Realism that asks the reader to forget the plot that rushes forwards with the time, and linger another moment in the eternal present. Curator: Jonathan Hirschfeld Read more  |

| all rights reserved - CAN ISRAELI ART REALITY |

| סייבורג מחשבים - בניית אתרים |